What really happens when you open up ESPN app on your iPhone

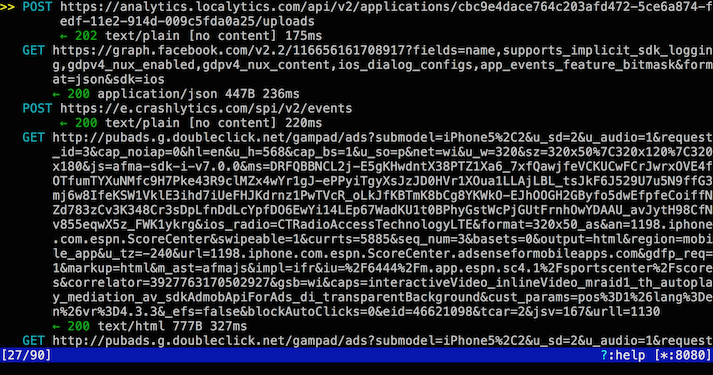

Occasionally, I analyze mobile apps to understand what is really going on behind the scenes knowing that the security and privacy of mobile apps are generally terrible. I have had the ESPN app on my iPhone for months (https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/espn/id317469184?mt=8). It is no secret that the ESPN website and their native mobile apps are riddled with ads –the question is how much ads. My favorite tool to analyze mobile apps is mitmproxy (https://mitmproxy.org/) to examine HTTP and HTTPS traffic. I was introduced to mitmproxy by Veracode and Mark Kriegsman back in 2012 when they analyzed which iOS apps were transmitting users’ address books. To learn how to set up capturing all HTTP and HTTPS traffic from your iPhone or any mobile device to mitmproxy running on a computer, here is a good article. The key is to install the mitmproxy certificate onto the mobile device (for iOS, see https://mitmproxy.org/doc/certinstall/ios.html).

With all HTTP and HTTPS traffic from my iPhone going to my laptop that has mitmproxy running, I opened the ESPN app on my iPhone. Between 04:19:58 GMT and 04:20:44 GMT on Wednesday, June 10th (that is less than a minute), the ESPN app made 90 requests. See list all requests made by the ESPN iOS app below (incomplete URIs); requests that have an asterisk are ad-related, Facebook included. So what kind of requests were made? Some for static content from ESPN’s content delivery network, some for app analytics, and many were ad related. Of the 90 requests, 60 were ad related. That’s ~66% of all requests when you just open up the app. Most mobile apps are just as bad, especially the freemiums. This was enough for me to delete the ESPN iOS app from my phone.

I posted the flow of all HTTP and HTTPS traffic from the ESPN iOS app for your analysis and interest: espn-ios.flow. This file has all the requests including complete URIs, HTTP and HTTPS requests and responses. You can open the file from mitmproxy.

GET http://cdn.optimizely.com/

GET http://scores.espn.go.com/

*GET http://ads.mopub.com/

GET http://scores.espn.go.com/

POST http://w88.m.espn.go.com/

GET http://scores.espn.go.com/

POST http://w88.m.espn.go.com/

GET http://api-app.espn.com/

*GET http://b.scorecardresearch.com/

POST https://e.crashlytics.com/

*GET http://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/

POST http://w88.m.espn.go.com/

POST http://w88.m.espn.go.com/

GET http://api-app.espn.com/

GET http://api-app.espn.com/

POST http://w88.m.espn.go.com/

GET http://scores.espn.go.com/

POST https://e.crashlytics.com/

GET http://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/

GET http://api-app.espn.com/

GET http://api-app.espn.com/

GET http://api-app.espn.com/

GET http://a.espncdn.com/

GET http://a.espncdn.com/

GET http://a.espncdn.com/

*GET https://googleads.g.doubleclick.net/

POST https://analytics.localytics.com/

*GET https://graph.facebook.com/

POST https://e.crashlytics.com/

*GET http://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/

*GET http://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/

*GET http://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/

POST https://e.crashlytics.com/

*GET http://ad.doubleclick.net/

*GET http://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/

*GET http://ad.doubleclick.net/

*GET http://ad.doubleclick.net/

*GET https://googleads.g.doubleclick.net/

*GET http://pixel.adsafeprotected.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://ad.doubleclick.net/

GET http://api.espn.com/

*GET https://googleads.g.doubleclick.net/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

GET http://scores.espn.go.com/

*GET http://pixel.adsafeprotected.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://sc.iasds01.com/

*GET http://dt.adsafeprotected.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET https://secure-us.imrworldwide.com/

*GET https://d.turn.com/

*GET https://secure-us.imrworldwide.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET https://secure-us.imrworldwide.com/

*GET https://secure-us.imrworldwide.com/

GET http://api-app.espn.com/

GET http://api-app.espn.com/

*GET https://pixel.adsafeprotected.com/

*GET https://pixel.adsafeprotected.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET https://secure-us.imrworldwide.com/

*GET https://secure-us.imrworldwide.com/

*GET https://pixel.adsafeprotected.com/

*GET https://pixel.adsafeprotected.com/

GET http://a.espncdn.com/

*GET https://www.facebook.com/

*GET https://d.audienceiq.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://core.insightexpressai.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET http://v4.moatads.com/

*GET https://pixel.adsafeprotected.com/